‘Death trap’ Channel boats traded by smugglers in German city

It costs €15,000 (£12,500) for the whole “package”, we are told. For that we would be given an inflatable dinghy, with an outboard motor and 60 life jackets, to get across the English Channel.

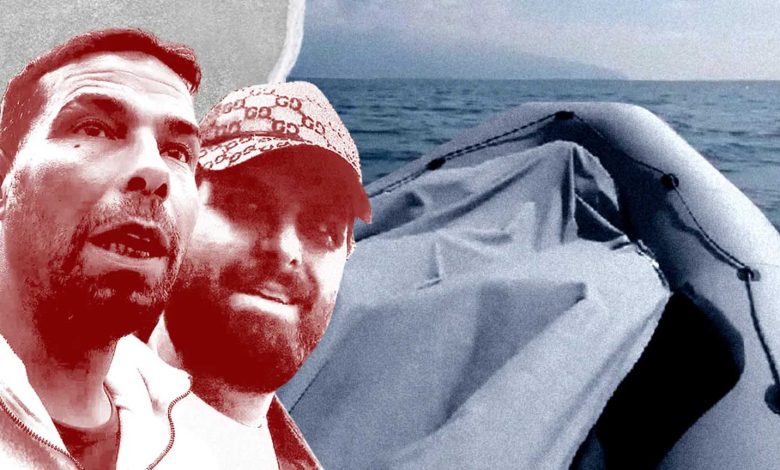

This is the “good price” offered by two small-boat smugglers to an undercover BBC journalist in Essen – a western German city where many migrants live or pass through.

A five-month-long BBC investigation has exposed the significant German connection to the lethal human smuggling trade across the English Channel.

As the new UK government promises to “smash the gangs”, Germany has become a central location for the storage of boats and engines eventually used in Channel crossings – confirmed to the BBC by Britain’s National Crime Agency.

During covert filming, smugglers revealed to us that they store boats in multiple secret warehouses – as they play cat-and-mouse games with German police.

This year is already the deadliest for migrant Channel crossings, UN figures show, while more than 28,000 people have so far made the journey in small, dangerously packed boats.

Our undercover reporter is waiting outside the central station in the city of Essen.

He is wearing a secret camera and posing as a Middle Eastern migrant, eager to cross the Channel to the UK with his family and friends.

He must remain anonymous, for his safety, but we will refer to him as Hamza.

He approaches a man. It is someone Hamza has been in touch with for months, via WhatsApp calls, after getting his number through a contact within the migrant community – but this is the first time they have met.

This man’s name – or at least the name he has given us – is Abu Sahar.

Since Hamza contacted him, they have discussed how Sahar can help provide a dinghy to get to the south coast of England.

Hamza has told him that bad experiences with the smuggling gangs in the Calais region have driven him, his family and friends to try to manage their crossing alone – an unusual step.

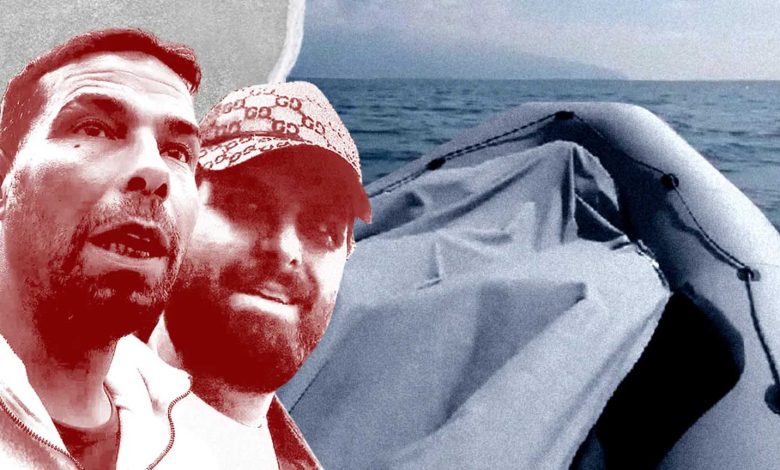

Sahar has already sent a video of an inflated dinghy which, he has suggested, is “new”, available and being kept in a warehouse in the Essen area.

He will go on to supply more footage including other, similar looking, boats as well as outboard engines being fired up.

Hamza has said he wants to check the quality of the items on offer himself and that is why he has insisted on an in-person meeting.

A BBC team is nearby, monitoring Hamza’s movements, in case anything goes wrong, or we need to extract him quickly.

As the two men walk through the centre of Essen, Sahar declares it is too “risky” to go to the warehouse to see the boat, even though he says it is less than 15 minutes’ drive away.

When Hamza asks about why the boats are kept in this part of Germany, Sahar talks about “safety” and “logistics”.

Essen is just a four- to five-hour drive from the Calais area – close enough to get boats there fast, but not too close to the more heavily monitored beaches of northern France.

While police raids do happen, the facilitation of people-smuggling is not technically illegal in Germany if it is to a third country outside the EU, which the UK now is after Brexit.

The interior ministry in Berlin argues that, because Germany and the UK aren’t geographical neighbours, “no direct smuggling” actually takes place – but a UK Home Office source told the BBC there is “frustration” about Germany’s legal framework.